Hope Is Contagious

By Asian Prisoner Support Committee

Illustrations by Natalie Bui

In Winter 2017, members of the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) went to visit their friend Borey “Peejay” Ai1, a Cambodian (Khmer) person detained at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) immigration jail in northern California. During the visit, it was clear that ICE had worn Peejay down: he was skinnier, his eyes bloodshot and droopy, his voice soft and muffled behind the visiting room glass. Peejay had been denied bond and had just lost his Convention Against Torture (CAT)2 case. All signs pointed to his imminent deportation.

It was in these moments that we began to search for hope on behalf of Peejay—and we found it in the hopeful struggles of the community around us: in Ny Nourn3, a survivor of domestic violence who fought ICE in a landmark case; in Khmer families in the Bay Area, who created a movement to free their loved ones; in Anoop Prasad4, a fearless immigration attorney and advocate; and in Peejay himself, who continues to fight against all odds. While most of APSC’s direct experience comes from organizing struggles in California, we were also inspired by Khmer anti-deportation organizing efforts in other states, like those of Many Uch5 in Washington and Jenny Srey6, Montha Chum7, and the campaign #ReleaseMN8 in Minnesota. Learning more about these freedom stories reinvigorated us to continue fighting for Peejay’s freedom and countless other Cambodian Americans who would be detained in subsequent ICE raids.

“When you talk to someone who has been down for decades and still has fight in them, you do not get to give up. So I fight alongside you and hope alongside you—even when it seems impossible. I carry your hope inside of me out of those prison walls. What you may not realize is that your hope is contagious.”

As deportations rise for Southeast Asian Americans, we want to show how families, organizers, and formerly incarcerated individuals have successfully fought for their freedom—and show that others can fight and win, too. The following stories highlight individuals who have survived, persisted, and resisted the many fronts of state-sponsored violence. They are stories of deep pain, stories of triumph, and most importantly, stories of hope. By sharing these stories with you, we hope that you find inspiration to fight for your freedom and the freedom of your loved ones.

Because when one person’s hope results in their freedom, hope becomes contagious.

“The practice of celebrating is hard when there are more people still detained or in danger of deportation. It’s easy to miss the miracle of the moment, when work remains, and so many others to get freed. So today I take time to celebrate the miracles that happen when we organize. There’s the miracle of Khmer elders and formerly incarcerated folks winning pardons through Governor Gavin Newsom for two Cambodian fathers. There’s the miracle of femme leadership, where partners and daughters who shoulder the impact of their loved one’s incarceration, turn what could be shameful into a loud demand for justice.”

Limbo

After serving a state prison sentence, many immigrants and refugees face a kind of double jeopardy. They are directly transferred from prison to immigration jail, where they stay incarcerated for an unpredictable amount of time. It could be months or even years. Some people have been imprisoned in ICE for over 10 years while fighting their deportation cases.

“It’s one of the toughest things you can do when you call your Mom and she asks when you’re getting out and you say you don’t know. Because in the state [prison] time, when they ask, you have a specific date whatever it may be. But when you are doing immigration time, it’s, ‘What do you mean you don’t know when you’re gonna get out?’ There’s this kind of limbo state. I didn’t really know what was going on, but I kept fighting and fighting.”

Many was immediately transferred to immigration detention to be deported to Cambodia upon his release from prison in 19978. Because Cambodia was not accepting any deportees at that time, Many was stuck indefinitely in immigration detention. He, along with many others participated in hunger strikes and a landmark legal challenge to indefinite detention, which finally allowed his temporary release in 1999. In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that no one could be kept longer than six months without reasonable possibility of being deported (Zadvydas v. Davis). Following years of advocacy, community building, and organizing, Many officially received a governor’s pardon in 2010, leading ICE to terminate his deportation case in May 2019.

Kites

Peejay and Ny were both survivors of the Khmer Rouge genocide and former “lifers” who were directly transferred to ICE at the same time. After hearing about Ny’s story through Anoop (who provided legal representation and advice for both of them), Peejay began to write to her, hoping to build another line of support to sustain them both.

Sending and receiving “kites” connects prisoners with the outside world, or even to another prison or jail. A handwritten letter means that someone is thinking about you.

“When she was going to her hearing, I wrote to her and wished her luck and sent out energy and prayer out for her. It was so joyful for me. She won, and it was so inspiring to me. It brings so much hope to know that we all fought for this; we’re not alone.”

Return

Leaving a prison or immigration jail can be bittersweet—freedom comes at the cost of leaving behind dear friends and loved ones, some of whom may remain incarcerated, and others deported to foreign countries far away. Ny Nourn, a former lifer and domestic violence survivor who won her deportation case, has continued to fight for other detainees after she was released.

Two Minnesotans, Jenny Srey and Montha Chum, had their husband and brother picked up by ICE for old criminal convictions. For people like Jenny Srey and Montha Chum, fighting for their loved ones resulted in the formation of the #ReleaseMN8—a campaign to release eight Cambodians picked up by ICE. They organized families in Minnesota and won the release of three people. They continue to support and fight for the five who were deported—and others who face similar struggles.

“Just keep going. If you get a no, don’t give up. Don’t think there’s nothing else you can do. Especially when you’re talking with elected officials, they’ll push back, but just remember it’s a ‘no, no, no,’ until it’s yes.”

Jenny Srey, Montha Chum, and Ny Nourn continue to fight for impacted folks who remain behind bars. They exemplify how women—those who have loved ones in ICE detention, and those who have endured the violence of the incarceration and deportation systems—are the ones who lead the charge in the anti-deportation movement.

“In my lifetime, I want to see folks having that right to return, and coming back to the U.S. to reunite with their families. That’s like a dream.”

“Believe that your freedom is possible, that you are worthy of a second chance.”

Hope Is Contagious

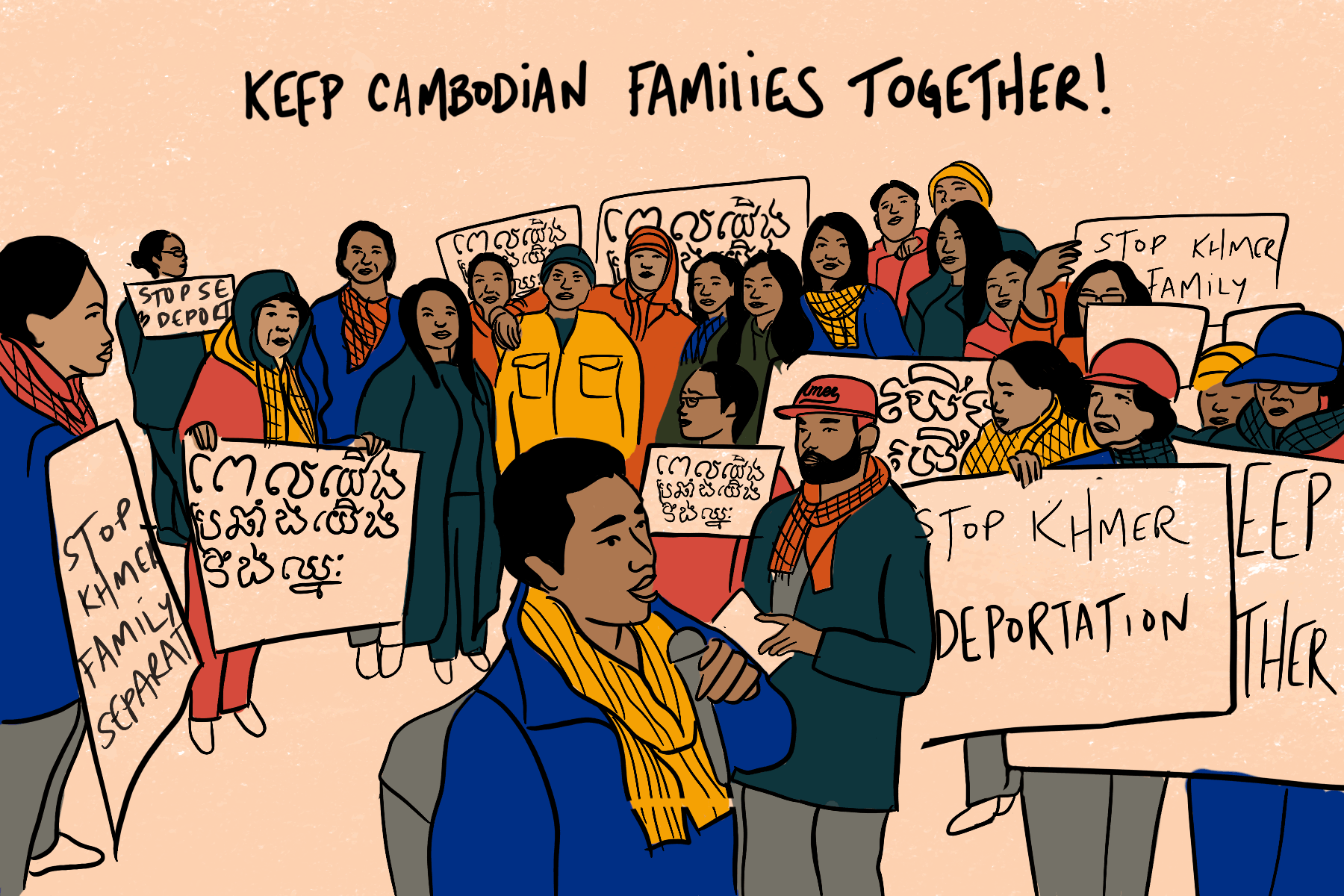

On March 13th, four Oakland Khmer community members were arrested by ICE in front of their loved ones. The Khmer elders felt the familiar pain of separation, a deep and scarred wound that went back to generations of war, genocide, and forced migration. They watched the younger generations, now cut by a similar pain of family separation. Our Bay Area Khmer community began to organize, mobilize, and protest against deportations in an unprecedented way; but the fight to keep our families together is not new. Time and time again, our community has drawn strength from the love of our families in the face of war, displacement, or ICE detention. They chose to follow hope.

“I am moved because our community stood by these families. They chanted, shouted and sang. We had to all force ourselves out of silence and practice to be activists. On March 13, we bridged the gap between the generations, melting the hearts of those who did not understand our struggles.”

“Cambodian refugees have always lived in fear. The community coming together felt like Cambodians were rising from death and coming to life. This was a rebirth for me. It brought back the strength that I felt I had lost over the years.”

Birds

“Bah Yung Pra Chang, Ung Niek Chanegh!” Families, friends, attorneys, and community members rallied at politicians’ offices, City Halls, and community centers. They were fighting to prevent the worst-case scenario—ICE deporting their family members to a country from which they had escaped as refugees many years ago. With uncertainty and fear thick in the air, families knew they had to protect each other, love each other, and fight for each other. This sparked the rally chant families shouted at countless actions, “Bah Yung Pra Chang, Ung Niek Chanegh. When we fight, we win!” This chant traveled from a family event at the Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants (CERI) office, to the San Francisco ICE facility, to the Governor’s office in Sacramento, and to Oakland and San Francisco City Council meetings. In response to the pressure, Governor Newsom issued two pardons, and two other Khmer detainees won post-conviction relief. When all four Bay Area Khmer detainees were freed and made safe from deportations, the community reunited and chanted one more time, “Bah Yung Pra Chang, Ung Niek Chanegh. When we fight, we win!”

“It was beautiful to witness the Cambodian community come together—youth side-by-side with the elders, crying out in Khmer: ‘When we fight, we win!’ Some of the first-hand accounts shared at the rally were probably shocking to the non-Cambodian allies present, but to our community, those stories were sadly all too familiar. Painful stories of trauma begetting trauma. That’s why it’s so important to come together to try to end that cycle, to fight against these injustices, and to heal our community.”

Community Photos

Nathaniel Tan visiting Borey "Peejay" Ai while in ICE custody in Winter 2017.

Hours after Peejay's release from ICE custody. Left to right: Tung Nguyen, Borey "Peejay" Ai, Ben Wang, Kasi Chakravartula.

After Mother’s Day Action on May 10th, 2019, Khmer mothers, aunties, and elders gathered to celebrate a successful rally and advocacy event to advocate for impacted community members to stay home.

Khmer mothers, aunties, and elders gather at Governor’s office to deliver petition and pardon applications of detained Bay Area Cambodians.

Organizers and advocates gather at Oakland City Hall and successfully pass resolution to condemn detention and deportation of Bay Area Cambodians.

Nathaniel Tan speaking at a rally in front of San Francisco ICE building during ICE check-ins of Bay Area Cambodians.

Community members, mothers, aunties, elders, and family members of impacted individuals gather at Center for Empowering Refugee and Immigrants (CERI) fighting for the release of their loved ones from ICE.

Bay Area community members supporting Somdeng Danny Thongsy #Stand4Danny at his ICE check-in in San Francisco.

#PardonRefugees campaign BBQ to celebrate the release and relief of Bay Area Cambodians facing deportation.

Take Action

If you are interested in getting involved or supporting this work, please contact us at info@asianprisonersupport.org and consider taking these next steps:

Read

“Worth Fighting For”

Profile on Jenny Srey and ReleaseMN8 by Chanida Phaengdara Potter

“This is the Story of Many Uch”

By Aditi Bhandari

“Writing Hope into Our History: Cambodian Deportation Defense Organizing”

By Nathaniel Tan

“Dreams Detained, in Her Words”

The effects of detention and deportation on Southeast Asian American women and families

A Report by SEARAC and NAPAWF (PDF)

“He was deported for a crime he committed at 19. Now a 30-year-old Cambodian refugee is back home in California”

By Charles Dunst, Los Angeles Times

“She (Ny Nourn) was sentenced to die in prison because she couldn’t control her abuser.”

By Anoop Prasad

Campaign & Tools

Sign the petition: Urge Governor Newsom to end California’s collaboration with ICE

#KeepTithHome #ICEoutofCAPrisons

Southeast Asian American Solidarity Toolkit

A Guide to Resisting Deportations and Detentions from the #ReleaseMN8 Campaign

Southeast Asian Raids

Resources for Refugees Facing Deportation to Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos

Guide to California Pardons

Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus